“To recognize that there is a need to distinguish…between the good and the evil in tradition, requires recognition of the preeminent role (not, lest I be misunderstood, the sole role) of reason in distinguishing among the possibilities which have been open to men since the serpent tempted Eve and Adam…” –Frank S. Meyer

Mom used to take me to bookstores on occasional trips to the mall or en route to some all-day set of errands. Barnes & Noble, Borders, some local community shop—I cared less for the name on the door than for the promises teased on back covers and inside flaps. She and I have long been avid readers, so these little sojourns to outposts of the empire of narrative were often my favorite part of an entire week. It’s a shame there were no frequent-traveler miles for wandering by print.

Years after our last trip together to whatever manuscript emporium, Mom bought me an eReader for Christmas. She asked me if I would use it. I told her I would, and I sincerely meant it. I have read a few books since that day. Not a one has lacked the tree-born pages so amenable to dog ears and annotation. It turns out that for all the time absorbed by the many screens in my life, I remained a reactionary on books. It was never even a conscious choice but simply a fact of me.

But the more I think on it, the more I find myself an unrepentant partisan of the traditional, battery-free book. The reason is not that I hate eReaders, want them to go away, or somehow associate them with civilizational decline—to the contrary, ebooks and other digital goods are the latest children of the mind, as worthy of celebration and use as their elder siblings. But in the end, the experience of a natural book is to the LED script of an ebook as the sound of your voice is to the lines of a text or as getting lost under the sky is to clicking through Google Maps Satellite.

It’s a bit like the ongoing conservation of conservatism.

On the one hand, you have traditionalists clinging to such antiquated values as family, honor, duty, loyalty, and transcendence because they speak holistically to the disparate and unified condition of humanity. Tradition, after all, is as much a project of aesthetics as of truth, as much for the heart as for the mind. It is the anchor of the eternally silent majority in cold, cosmic seas—the balance of agency and cupidity in the present by the democracy of the dead.

An eReader battery dies or “digital rights” management prevents you from sharing your ebook with a friend. But at any time you can read a paperback and give it to anyone as readily as your community imparts the peculiar stamp of its wisdom and flaws. A dog-eared page can trigger memories or fantasies as poignantly as a photograph in a loved one’s home. The annotations on paper are as stories told across decades, iced tea, pecan pie, and the background sound of children playing. There is something ineffably raw about a book that is lost in translation to yet another screen between you and the escalating abstractions of a rapidly digitizing world. There’s something about the way the markings and the mass carry separate, wordless stories of joy and pain, vulnerability and hope.

On the other hand, you have libertarians beating the drums of pragmatism, efficiency, liberty, idiosyncrasy, and autonomy. Denying sentiment, they offer function. Against reaction, they demand solutions. No longer impressed either by tradition—and underlying assumptions of old authority and static truth—or establishment—and its atrophic will to complacency—they seek above all freedom from imposed shackles and entrenched stupidity.

A book is a tool to impart knowledge or provide entertainment. Where we progressed from vinyl to cassette tapes to CDs to iPods, we have evolved from oral tradition to manuscript to paperbacks to ebooks. Our lives are more efficient, our opportunities more plausible, our tools more expansively useful when technology captures libraries in the palms of our hands. There is something uniquely enabling about the power to construct and define your own domain in an increasingly automated society.

Where these perspectives meet is in the question central to the whole project of free society, and the narratives it keeps—what is freedom for?

Is it really convenient to have a universe in a Kindle if you no longer know the spontaneous pleasure of glancing at a shelf, grabbing an inviting title, and reclining into a place where the smells of wood, paper, and earth create worlds within worlds of imagining? Are you really better off if you no longer find reason to flip through an old favorite and reminisce over highlighted passages that once breathed clarity into vast labyrinths of mystery? Are you freer if your autonomy comes in automated packaging that will wipe away its every memory of you under the commands of a stranger? Under all the paeans for progress and efficiency, are you any less of a hopeful machine wanting pieces of the world to retain some piece of you when you’re gone? Or will we have people autograph our eReaders now?

I’m not saying abandon your Nook and your smartphone and read only through disposable media. I rarely read print news anymore at home, but I would be remiss to deny preferring the touch of an express paper to my smartphone on the morning Metro. I would never want to live in any dimension where the expanse of human knowledge is beyond reach of my hand. And I would not care to endure an era where all simple joys of old pleasures were ever abandoned for newer toys. What I cherish is knowing that the convenient genius of an eReader is always within reach, even as I freely choose to seek my stories elsewhere.

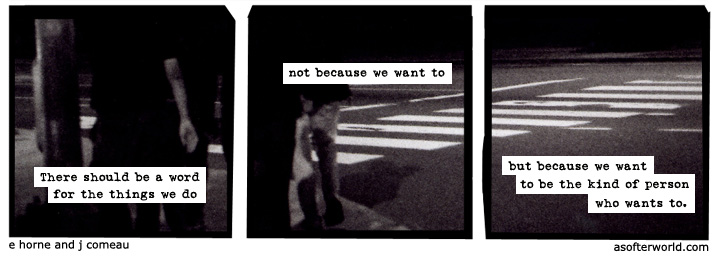

There should be a word for the things we do, not because they’re sensible, but because we want to.

This post was written in response to the Weekly Writing Challenge from The Daily Post.